It is difficult to know what to post about a man whose life and work have reached such mythic proportions as Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. In literature, he is best known for his novels Gulag Archipelago, written between 1958 and 1968 and published in 1973, and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, published in 1963.

The two novels are based on his years of imprisonment in a Soviet labor prison camp from 1945 to 1953. He was arrested and imprisoned for anti-Soviet propaganda and remarks made against Stalin discovered in correspondence to a school friend. After his eight-year imprisonment ended in 1953, he was sent into exile in Kazakhastan, on the fringes of Siberia. In 1956, he was freed from exile and exonerated. In trying to publish his work over the next 18 years, he was persecuted by the KGB, arrested again in 1974 and deported to West Germany. He then moved to Zurich, Switzerland, and later to Cavendish, Vermont. In 1990, his Soviet citizen was restored, and he returned to Russia in 1994.

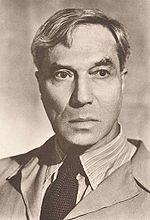

Solzhenitsyn after his release in 1953. He smuggled out his padded jacket and number patches and had his photo taken.

In Solzhenitsyn’s book Voice from the Gulag, he said, “Over a half century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of old people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened. Since then I have spent well-nigh 50 years working on the history of our revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.”

And in his Nobel lecture, “During all the years until 1961, not only was I convinced that I should never see a single line of mine in print in my lifetime, but, also, I scarcely dared allow any of my close acquaintances to read anything I had written because I feared that this would become known. Finally, at the age of 42, this secret authorship began to wear me down. The most difficult thing of all to bear was that I could not get my works judged by people with literary training. In 1961, after the 22nd Congress of the U.S.S.R. Communist Party and Tvardovsky’s speech at this, I decided to emerge and to offer One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Such an emergence seemed, then, to me, and not without reason, to be very risky because it might lead to the loss of my manuscripts, and to my own destruction. But, on that occasion, things turned out successfully, and after protracted efforts, A.T. Tvardovsky was able to print my novel one year later. The printing of my work was, however, stopped almost immediately and the authorities stopped both my plays and (in 1964) the novel, The First Circle, which, in 1965, was seized together with my papers from the past years. During these months it seemed to me that I had committed an unpardonable mistake by revealing my work prematurely and that because of this I should not be able to carry it to a conclusion.

It is almost always impossible to evaluate at the time events which you have already experienced, and to understand their meaning with the guidance of their effects. All the more unpredictable and surprising to us will be the course of future events.”

The following excerpt is from Solzhenitsyn’s novel An Incident at Krechetovka Station in his book We Never Make Mistakes, published in 1971 and translated by Paul W. Blackstock:

The following excerpt is from Solzhenitsyn’s novel An Incident at Krechetovka Station in his book We Never Make Mistakes, published in 1971 and translated by Paul W. Blackstock:

“Only the people who worked at the station were not driven away by the rain. Through a window a watchman could be seen on the platform near the rain-drenched cargo. Covered with a heavy tarpaulin, he stood there all wet and soaked from the rain without even trying to shake it off. On the third track, the switch engine was slowly moving a tank car, while the switchman, covered entirely with a hooded poncho, waved to him with his flagstick. The dark, dwarfish form of the wagon master could also be seen walking along the train formation on track two, looking and searching under each car.

And so — everything was rain-drenched! In the cold, persistent wind, the rain beat on the roofs and walls of freight cars and the engines. It cut along the fire-red, bent-iron ribs of two, ten-car skeletons (some for the boxes were still burning from the bombing raids, but the useful parts of those remaining had been brought to the rear). It drenched the four Artillery pieces standing on flatcars; it blended with the approaching twilight; it began to tighten and close in on the green, small circle of the semaphore, and on the livid, purple-red sparks which were flying out of the chimneys of the ‘heated’ cars. [These were boxcars adapted for troop transport which in cold weather were fitted with makeshift stoves, with long thin pipes for chimneys that extended through the roof.] All the asphalt on the first platform was covered with crystal-clear water blisters, which had not had time to drain. Even in the dusk the rails glistened and sparkled with bubbles, and all the gray storm covers shimmered with pools of water.

There was little sound besides the trembling of the earth, and the weak sound of the switchman’s horn. (Whistling by the engines had been forbidden since the first day of the war.) Only the rain trumpeted through the broken pipes.

Behind the other window of the Commander’s room, in the path along the warehouse enclosure, grew a small oak. Its drenched and trembling branches had held a few dark green leaves, but today even the last few had blown away.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.